Take Five

An Architecture for Mathemagenic Learning

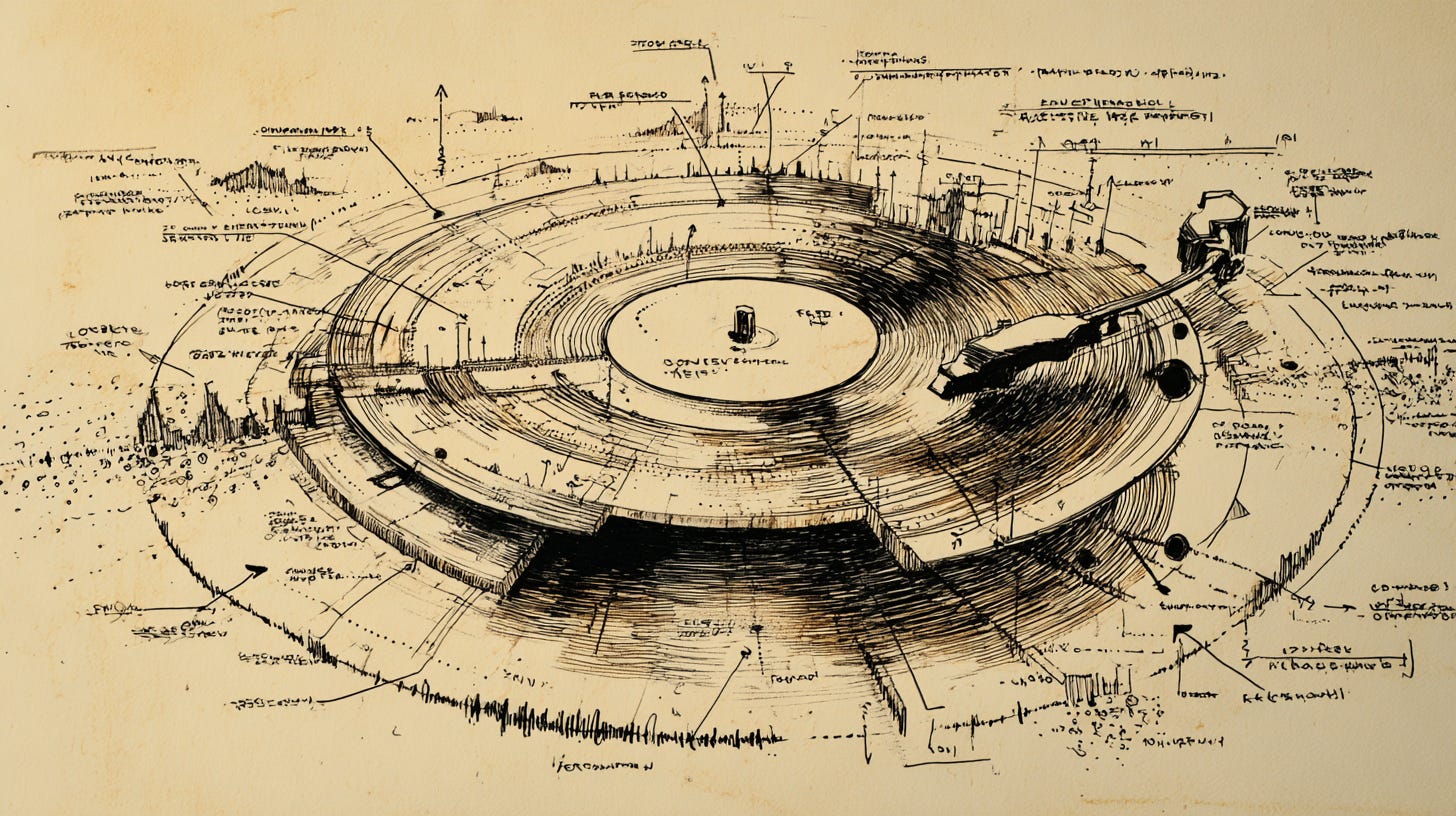

On the podcast Song Exploder, musicians open the hood of their own tracks—isolated vocals here, that weird synth line there, the drum loop they almost deleted but kept because something about it worked. It's not quite a tutorial. It's more like watching someone say, "Here's where I made a choice I can't fully explain, and here's where I knew exactly what I was doing."1

I’ve been thinking about what that would look like for teaching. Not the polished lesson plan we submit for observation, but the actual architecture of how we design moments where students might—might—actually learn something.

Which is why I keep coming back to a term coined in 1970 by a psychologist named Ernst Rothkopf: mathemagenic activities.2 The word essentially means “giving birth to learning.” Rothkopf’s insight was deceptively simple: you can deliver all the content you want, but learning depends on what the learner does with it. Students have veto power. They can sit through your beautifully crafted lesson and walk away with nothing, because learning isn't transferred—it's constructed. But not by us. By them. And that's the problem: we spend enormous energy on delivery and almost none on what students actually do with it.3

In my experience, spanning twenty years in a history classroom, the delivery method often matters less than we think. Whether you're lecturing or facilitating, the same problem persists: we design instruction around what we'll say and do, not around what students will think and process. Then we're surprised when assessment reveals they can't actually use the content.

So I started designing backward from student cognition instead of forward from my delivery. Not “what will I explain?” but “what will they do with it?” That shift—from content delivery to cognitive activity—is what mathemagenic design actually means.

So what follows is me doing a kind of Song Exploder on my own history classroom. Here's the architecture I use, built around Arthur Shimamura's MARGE model—five cognitive moves that give mathemagenic activities their structure. Think of it as though I was playing jazz. Yes, there's a foundational structure, but I'm reading the room and deciding what to emphasize, when to linger, when to shift. Shimamura gives me the framework; the classroom gives me the improvisation.

The Five Moves

M is for Motivate. This is setting the table for attention. In a world where my students carry supercomputers designed by teams of engineers optimizing for engagement, I’m competing with TikTok using... a whiteboard and my personality.4

Motivation starts with a good question. Not a review question—a hook question. Something that creates genuine cognitive tension. “Why would a country abolish slavery and then immediately create systems that functioned almost identically?” That’s not asking what they know. That’s asking them to hold a contradiction. Attention follows contradiction.

A is for Attend. Here’s where I use constructive retrieval—students recall information about a term or concept before we build on it. Not “who can tell me about Reconstruction?” but “write down three things you remember about the Freedmen’s Bureau without looking at your notes.”

The act of retrieval isn't just assessment—it's a learning event. Every time they pull something from memory, they're strengthening the pathway. But I'm not asking them to struggle with recall. I'm asking them to struggle with meaning. Retrieval clears the deck so they can think historically, not just remember historically.

R is for Relate. Once they’ve retrieved the raw material, they need to connect it. Think historically: identify cause and consequence, yes, but also trace continuity and change over time. What persisted? What shifted? This is where I ask them to do the work of a historian: not recite facts, but construct meaning from them.

The Attend-Relate sequence is my foundational riff. If you walked into my classroom on any given day, this is what you’d see most: students recalling a term, then thinking historically with it.

G is for Generate. This is where students produce something using the content we’ve covered. And honestly? This is where they struggle most. I’ll ask them to write a newspaper headline representing a particular historical perspective—a Northern abolitionist paper in 1866, a Southern Democratic paper, a Black-owned paper in Philadelphia. Same event, different framings.

They find this hard. Which tells me it’s exactly the right kind of hard. Generation forces them to transform information, not just hold it.

E is for Evaluate. This year, I’ve leaned heavily into this letter. Given the informational landscape of 2026—where AI can produce fluent nonsense and confident misinformation travels faster than careful correction—I’m incraesingly teaching students to identify false historical claims. We look at viral posts, AI-generated “facts,” and practice the question: How would I verify this?

But there’s another layer here, maybe the more important one: metacognitive self-evaluation. “Do I actually know this, or am I recognizing it because AI just told me?” In a world where you can outsource cognition, the question “what do I actually understand?” becomes survival-level important. That’s the new work of Evaluate—not just checking the source, but checking yourself.

Holding it Loosely

Crucially, here’s the thing I hold loosely: MARGE isn’t a checklist. It’s more like a jazz chart. There’s structure, yes, but the structure breathes. I create space—almost like a jazz musician—for what’s needed in a particular moment, given what instruction has happened and what students are giving me. Some days the class needs more Attend. Some days we stay in Generate longer because the struggle is productive. Some days Evaluate takes over because someone found something online that needs to be interrogated together.

The Song Exploder metaphor works because it makes the invisible visible. When Hrishikesh Hirway asks a musician “why this chord change?”, he’s asking them to articulate what’s usually tacit. That’s what I’m trying to do here—not because my approach is correct, but because making our instructional design explicit is how we get better at it.

So that's where I'm going to keep it. Five letters. A structure that breathes. A classroom where the architecture is intentional, but the improvisation is real—and where students occasionally surprise themselves with what they can do when they're asked to actually think, not just listen.

Note: I always pull blog titles from song titles or lyrics. It’s a thing. It’s fine. Just go with it. I named the blog “The Academic DJ” after all.

Today’s title comes from Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five”—jazz in 5/4 time, which shouldn’t work but does. Five cognitive moves in MARGE. A structure you can improvise within. The parallel wasn’t planned, but I’ll take it.

Shoutout to Matt Johnson from Loomis Chaffee’s CTL for this Song Exploder through line. I’ve been sitting on a version of this post for a bit, but a recent conversation with him unlocked this entry point and metaphorical spine.

I should note that Rothkopf begins his paper with one of the greatest sentences in human history when he writes, “Psychologists write from time to time in the human language.” He also points out the line that inspired him to write this: “You can lead a horse to water but the only water that gets into his stomach is what he drinks.” This is also a certified banger.

I'm not interested in litigating constructivism vs. other learning theories here. The point is simpler: students have agency in whether and how they engage with what we teach. Call that construction, call it processing, call it whatever—the core insight remains that learning depends on what the learner does, not just what the teacher delivers.

The personality is doing a lot of heavy lifting here. And aside from incredibly nauseating Dad jokes, there’s not a lot to work with.