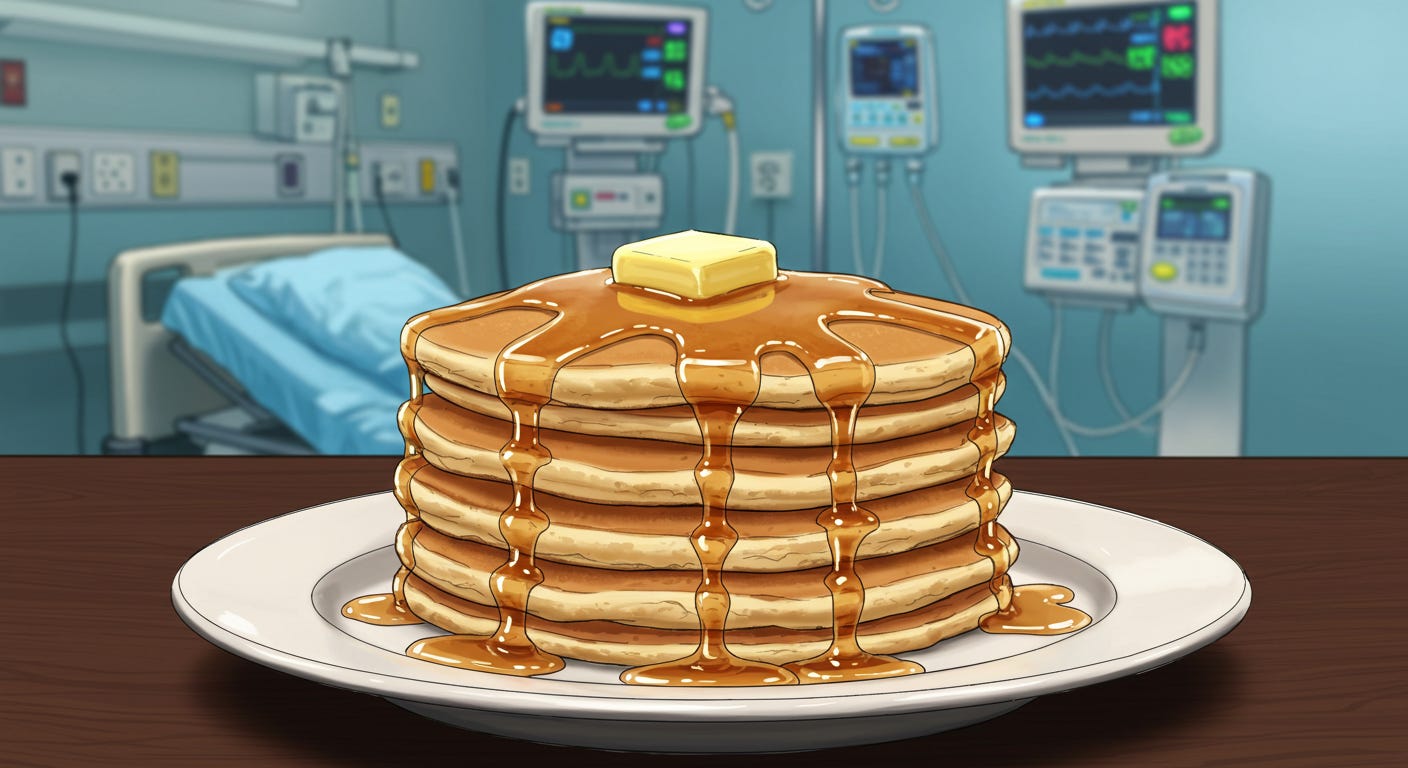

How do you measure a life? For me, the answer is pancakes. Not in some philosophical, abstract sense, but in the very real stacks of golden rounds I've piled over the last ten years. Each one marks a weekend morning with a sleepy-eyed toddler perched on a stool beside me, or a chaotic school-day breakfast where syrup was the only thing holding the morning together. While the past decade could be measured in milestones—recovery benchmarks, professional achievements, the relentless march of birthdays and anniversaries—I find myself drawn to these smaller, sweeter moments. These little rituals that, when stacked together, tell the truest story of my life since December 17, 2014.

Today marks the ten-year anniversary of my traumatic brain injury. I suffered a skull fracture and epidural hematoma while coaching an ice hockey game—a freak accident that very nearly ended my life. It was also, ironically, the best thing to ever happen to me. The day of my injury wasn't just about what was lost, but what would be found. There's a peculiar clarity that comes with brushing up against mortality, though this isn't an attempt to articulate it. Instead, this is my brief reflection on a decade of learning, living, and making pancakes.

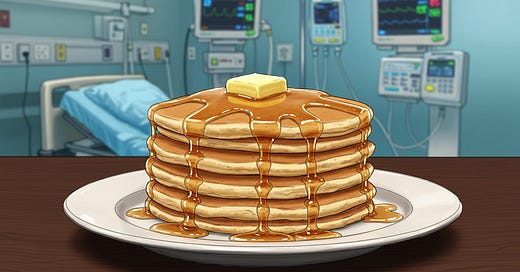

One of my clearest memories post-injury was my first meal after being extubated—a simple serving of hospital pancakes.1 That initial bite, sharp with sugar and possibility, electrified my dormant senses, thrusting me back into consciousness. After hours of tubes and IVs, this simple act of eating—so fundamentally human—was more than physical nourishment. It was a reclaiming of autonomy.2 Each syrup-drenched bite declared: I am here. I am alive. This wasn't merely a meal; it was as though I was experiencing the divine.

But recovery, like the perfect pancake, doesn't follow a precise recipe. In addition to the pronounced scar from brain surgery, there remain a handful of invisible marks—lingering effects unseen but felt.3 I've learned to embrace both, finding myself more alive because of them rather than despite them. That our first born would enter the world only ten days after I was discharged from the Neuro-ICU would merely amplify the experience. As he was learning to live life, so too was I relearning how to navigate a new reality—both of us orienting our place in a world that felt routinely alien.

In those early days, I often found myself searching for concrete ways to measure my improvement, to quantify how far I'd come. But I soon discovered that progress in life—whether measured in cognitive milestones or pancakes—defies easy quantification. Goodhart's Law tells us that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. The same applies to healing: the most meaningful growth happens not in rigid metrics, but in the soft, unexpected spaces between. For me, those spaces often smell like sizzling butter on a hot pan and end with sticky-fingered hugs.

Time meanwhile, much like crafting the perfect pancake batter, refuses to conform to rigid expectations. It loops and winds, speeds up in moments of joy and slows in reflection, often escaping the neat tick marks we try to impose upon it. These meandering moments—filled with the scent of cooked batter and echoes of laughter, marked by the slow drip of syrup—showcase not just my healing, but how fully I've lived. I've learned to recognize and cherish the fleeting moments that enrich our lives—connections made in passing, conversations that drift into raucous laughter, and stolen moments that linger in memory. Recovery taught me that dwelling on the past sinks us into melancholy, while fixating on the future breeds anxiety. These pulls—backward to sadness or forward to fear—only highlight the importance of now. Each brief snapshot of joy, no less significant for its brevity, reminds me to value the present, even in its impermanence.

As this decade culminates, I pause to appreciate these simple markers of time. Those stacks of pancakes speak to more than just recovery; they tell stories of love, connection, and the subtle joys that shape a life well-lived.

Later on I'll stand at the stove again, my cast-iron skillet seasoned by a decade of memories.

Because tonight, we’re making pancakes.

Note: I always pull blog titles from song titles or lyrics. It’s a thing. It’s fine. Just go with it. I named the blog ‘The Academic DJ’ after all. Today’s title comes from ‘The War on Drugs’ and their 2014 song, “Under the Pressure.” The song is a part of their 2014 album Lost in the Dream. I was injured late in 2014. It is safe to say that I’ve listened to this song more than any other song over the last decade. Below is a link to a live version of the song from 2018, because live music is awesome and this version absolutely rips.4

Extubated is the opposite of intubated. I had a breathing tube removed roughly 24 hours after being placed on a ventilator and emergency brain surgery. There’s a really comical story about me trying to scratch the back of my throat with a butter knife shortly after being extubated that deserves another 1,000 words on its own. Clearly, I was not operating at peak cognitive capacity at this point.

I might be using “autonomy” here loosely. Coordination was still very much a problem. But I could (mostly) grip a fork. Loosely.

For example—I can’t open things with my left hand. Twist caps? Opening a bag of chips? Forget it. My pincher grip over there is not so great. I also can’t hear very well due to lingering damage related to auditory processing in my brain. So too do I struggle with rampant tinnitus and hyperacusis, a hearing disorder that makes everyday sounds seem uncomfortably loud or painful. Even ten years later I still have bad days physically, cognitively, and emotionally that require me to shut down. These days are fortunately few and far between. But they still happen. Some scars are seen. And some are unseen.

Inject from 6:42 to the end of the song directly into my veins, thanks.